One of the things that People Like You has been looking at since the start of the project four years ago has been how qualitative and quantitative relationships are being brought together in novel ways. Contemporary practices and processes of personalisation in different fields, ranging from digital media to public health, data visualisation, cancer treatment and portraiture are explored in the blog series. The project has looked at how society is contained in different formations and positions of personhood, as well as looking at how persons can form societies in a multiplicity of ways. A sustained claim throughout the project has been that how persons or individuals and societies are brought together in relations has changed significantly since the emergence of the nation state and the very particular political arithmetic that accompanied such emergence, an arithmetic deployed in different spheres of public life for governing and modulating populations.

Race, gender and class have been at the heart of such constructions and classifications of systems of difference in Western societies (Haraway 1991), that is, nominal ways of categorising elements or units according to socially and politically defined qualities or kinds. Although qualitative in their formation and construction, these classifications of systems of differences have always worked hand in hand with classifications of systems of quantities and ordering like ratios, proportions, ranks, commensuration, and so forth.

In a blog post for the project back in March 2019, Celia Lury noted that in the last few years we have seen the emergence of a range of categories that overflow the traditional gender categories of women and men. Helen Ward and Rozlyn Redd also pointed at the formation of new health or medical categories as a consequence of the Covid pandemic. In a recent paper by Thao Phan and Scott Wark, the project looked into how the deployment of ethnic affinity categories in machine learning enable a redefinition of what we understand as race.

These new modes of categorisation are disconcerting, and we find ourselves many times in Goffmanian natural experiments, as when, for example, using gender neutral toilets and encountering persons of other genders than the ones we identify with, we wonder for a second whether we have chosen the wrong toilet by mistake. Similarly disconcerting and embarrassing is when we incorrectly address someone using the wrong pronoun, and we can hear the traditional binary category distinctions rattling and shaking silently, haunting us in the background.

We also have also the possibility of inhabiting other forms of collectives and plural formations that exceed gender, class or race individually, of being commensurate and grouped together with people we never thought we would have affinities with, or with people we always wanted to have affinities with, but we were never grouped with before. A recent controversial #intersectionality TikTok video with 217.1 k likes and 20.3 k comments stated:

‘Cc: I’m definitely going to get a lot of hate for this but

Can we talk how men of color & white women are kinda the same?

I know they are not the same but idk the way they both don’t understand intersectionality,

Or the way they weaponize their privilege while simultaneously victimizing & centering themselves?

Just a thought’

At other times, we find ourselves uncategorisable, in desperate need of a category to hand, or a sense of belonging, if the two have anything in common. A Twitter user during the pandemic said:

I feel like almost all of my closest professional friends are pro-vax, anti-vax mandate, mask-sceptical, anti-school closure (My governor is, too). This set of positions should have a name.

This social shift towards generating new modes of categorisation and other modes of addressing people is quite clear in the use of inclusive language, also referred to as neutral or generic language, which is spreading in different countries, particularly those with languages still structured around masculine and feminine grammatical forms. This is not only a shift towards incorporating, referencing, signalling other gender categories beyond the traditional binary distinction between female and male, but also a shift towards rearticulating the relationships between kinds or categories in relation to singular and plural formations – redefining the relationships between qualities and quantities. In this sense at least, grammar might have much more in common with political arithmetic than we might initially be willing to accept.

These relatively new uses of the plural and singular in relation to gender categories do not entail an assertion of the singular over the plural, or an obliteration of singular forms by plural formations, but a very different coming together of the relationship between individuals and their identities on the one hand, and the collectives or plurals they become part of on the other. Who and what is in the containment of singular and plural grammatical formations and language uses is certainly up for grabs.

Through inclusive language, a singular person can be designated to partake in a plurality of unspecified genders as when the pronoun “they” is used in its singular form in English; or when the singular pronoun “elle” is used in a similar way in Spanish. Additionally, with the use of genderless plurals like “nosotres” (we) in Spanish, an indefinite multiplicity of individual genders (and arguably other identitarian expressions) can be contained as part of a collective. The “dividual” Melanesians that Marilyn Strathern describes (1988) would certainly relate to and understand these identifications and belongings.

The example I want to highlight is inclusive language and its use in Spanish Argentinean, as the use of such linguistic forms has been highly contested and controversial. To think through these changes, I had the chance of speaking with two linguists in Argentina, Sofia De Mauro and Mara Glozman. Both of them are currently working on trying to understand and examine inclusive language discursive formations and use in the country.

During a first interview I spoke with Sofia De Mauro who is the editor of a recent essay collection entitled Degenerate Anthology: A Cartography of “Inclusive” Language. She is a post-doctoral Research Fellow at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina and a Lecturer in Social Linguistics at the Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities of the University of Cordoba, Argentina.

For the second interview I had a chance to speak with Mara Glozman who is a researcher at National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina and a Professor in Linguistics at the National University of Hurlingham (UNAHUR) in Buenos Aires. She has also been advisor to Monica Macha, an MP in the country who has proposed to legally introduce changes so that the use of inclusive language is officially accepted and recognised as a right of expression in different public Argentinean institutions.

As Amia Srinivasan notes in her insightful and fascinating piece on pronouns, language is nothing more (and nothing less) than a public system of meaning, a system that has been implicated in establishing particular relationships between individuals and groups, the one and the many, the singular and the plural as much as arithmetic has. The rules of grammar only make sense and work effectively if they are publicly shared and collective, and they become politically, if not evolutionarily (!) embedded and reproduced in the grammatical structure of a given language and its use at a given point in time.

In language use, both qualities (the gender attributed to persons and things for example) and quantities (whether words refer for example to one person or more than one person in the use of the plural and/or singular) work together by specified and agreed orderings, designations, and rules. In English, for example, there are two grammatical categories of number: that of the singular (usually a default quantity of one) and that of the plural (more than one). In English, the grammatical categories of gender are for example binary (she/he) only in the singular form. How plural and singular forms are combined with gender forms varies according to different languages. In the grammatical Spanish advocated by the Royal Spanish Academy, an institution that promotes the linguistic regulation and standardisation of the Spanish language amongst different cultures and countries, both singular and plural pronouns are gendered whilst nouns are also attributed with binary genders, although somehow arbitrarily.

Spanish also lacks a third person singular (or what has been defined as a third gender) that refers generically, as in English, to all non-human things and creatures (often excepting pets and sometimes ships) whenever the gender happens to be unknown: “it”. In Spanish, in contrast to English, every noun is designated with an arbitrary gender, even when inanimate. Tables, beaches, giraffes and imitations in Spanish are for example feminine. Water, monsters, hugs and heat are on the other hand masculine.

As in English, in Spanish the third person singular (ella/el; she/he) denotes a binary gender distinction. Unlike in English, in Spanish the plural pronouns “we” (nosotros/nosotras), “you all” (vosotros/vosotras), and “they” (ellos/ellas) need to be changed to match the gender of the group being spoken about or referred to. This is achieved by using the letter “a” when referring to feminine groupings, whilst the letter “o” is used when referring to masculine groupings.

If a group of persons varies/is mixed in gender, in Spanish the masculine form is used, as when in English “you guys” is used for a mixed group (as opposed to “you girls” or “you all”). Similarly in English, it has been widely accepted that when offering and using a singular but generic example in order to personify in writing and speech, “he” was used by default.

It is still the case that when referring to groups of people composed of multiple/more than one genders, the traditional grammatical Spanish rule dictates the use of the masculine and “o” to designate plural generics: los Latinos (the Latins); los scientificos (the scientists); los magos (the magicians). In recent years however, particularly in Argentina but also in other Latin American countries, a social and linguistic movement has started to emerge that proposes to replace with an “e” or other marks such as “x” or “@” not only the ordinary gendered way of referring to non-gender specific plurals in the masculine “o”, but also to groupings in both the binary feminine “a” and masculine “o”.

A few days into the first lockdown in Argentina, in a speech addressing the nation about the pandemic, president Alberto Fernandez referred to the population of the country not as Argentin”o”s and Argentin”a”s (to include both men and women) but as “Argentin”e”s (somehow controversially closer to the English the “Argentines”). A myriad of legal initiatives and inclusive language guidelines in the country have promulgated the replacement of “a’s” and “o’s” by “e’s” in an attempt to make Spanish both less binary-gendered and more inclusive (see my interview with Sofia De Mauro for more on this).

However, these initiatives have also been legally and publicly repudiated by a range of different actors and have generated a backlash and a stringent call for support of traditional Spanish grammatical forms from some social groups. To counterbalance the threat posed by this backlash, a recent legal initiative led by several MPs is intending to pass into law the right of expression in inclusive language in public institutions in Argentina. In the most recent developments, however, the government of the City of Buenos Aires has banned the use of inclusive language in all of its schools and learning materials.

The quest to define and promote a more inclusive, neutral or generic Spanish is having repercussions not only in Latin America but also in the USA where journalists, politicians, scholars and also official dictionary entries are for example proposing the use of the word Latinx. The replacement of the “o” by the “x” is an alternative to Latino, the masculine form used to designate “everyone” with a Latin American background (what constitutes a Latin American background and who can call themselves Latinx is a different story).

Similarly in the UK, in 2020 an initiative took place to petition the government to include Latinx as a gender-neutral ethnic category. The petition read: ‘I want the UK Government to acknowledge the huge population of Latinx/Hispanics here in the UK by adding a box allowing us to specifically designate this as our ethnic origin in the census form. We are not White, Black, Asian, and certainly not “other.”’

The Royal Spanish Academy has refused to accept these linguistic changes, in particular the use of the “todes” (everyone) in its generic form (as opposed to the feminine “todas” and masculine “todos”). The argument is that the institution itself cannot impose these changes top-down but that they will be officially accepted once Spanish gender-neutral language ‘catches on’ with Spanish speakers in the same way as other novel words have (see my interview with Sofia De Mauro for more on this).

‘Bitcoin’ and ‘webinario’ have, however, been recognised since 2021 as linguistically Spanish (and also attributed some arbitrary gender!) due to their supposedly extended and distributed use. It is unclear however, how many times linguistic expressions need to be used and in what contexts for the Royal Spanish Academy to include them as official Spanish words. Nor is it clear whether this would be an important or relevant milestone for the inclusive language movement in its Spanish version and specificity (see my interview with Sofia De Mauro for more on this).

During my interview with Mara Glozman it became clear that the collective meaning and use of “e” as an inflection in both the singular and plural is still in flux in Argentina. In certain uses, the inflection “e” appears to be a way of avoiding the use of the generic plural in masculine “o”, a form which has, in certain feminist understandings, made persons who identify themselves as women “invisible” (for a discussion on visibility and invisibility in and through language see my interview with Mara Glozman). In other uses, the plural generic “todes” (everyone) is intended to include multiple variants of gender without any particular specification of the gender to which this plural refers. Then there is the plurality in the use of plurals too: “todos”, “todas” and “todes”. In certain cases, “todes” is only used when intending to refer to self-identified non-binary persons.

The effects of the uses of “todes” are different of course when persons do or do not self-identify as non-binary. In some instances, for example, the use of the inflection “e” has been deployed to refer to collectives of trans men who would never self-identify as non-binary and for whom such denomination would be offensive. There is also, as Mara Glozman pointed out, the use of the “e” in “just in case” instances when heterosexual cis persons use these inflections when it becomes unclear to them, from an a priori heteronormative standpoint, whether someone might “fit naturally” with either feminine or masculine modes of address.

As Mara Glozman mentioned during our interview, there is an urgency for some to fix and stabilise meanings in language and speech – but this approach does not do justice to the multiplicity, variability and indeterminacy that discourses, language and its uses both necessitate and facilitate and that inclusive language clearly makes explicit. The political richness of this indeterminacy of language, but arguably too, the political richness of the indeterminacy of identity which many social and anthropological theories have pointed to – appear to rub against some inclusive language tendencies that attempt to fix and outline the meaning of genderless pronouns once and for all.

Also at stake in inclusive language, understood as a political movement, is the gesture towards expanding traditional bounded systems of categorisation and identification, like the binary female/male, and replacing them with a boundless and unlimited array of possible gender and identitarian options. Another gesture implicated in the inclusive language movement is the idea of self-identification which goes hand in hand with the right to be named and addressed in a person’s own terms (a right that binary people already clearly have).

Persons in this sense/view should be able to define themselves as they want when they want, interchangeably at any point in time, and they have also the right to be addressed by others in such a way at any point in time. Some, however, might choose to not reveal their gender and other identitarian forms of identification and address, and might want to remain unclassifiable in public, and expect that others should also consider this when addressing persons in their own presence (or not!) in front of others.

As Amia Srinivasan points out, a way of attending to such issues of language use when the structures of gendered language are still rattling and shaking in the background is to resort to the use of personal names in order not to break any of the (new) rules and disrespect anyone. Personal names are, however, not completely devoid of social connectedness either (for good and for ill). Personal names are after all implicated in bringing together “I” and “We” identity in making kinship, class and race relationships with others as well as individuality and singularity. Unsurprisingly, the constitution of personhood through personal naming is also linked to the emergence of the modern state, as the legal requirement to have a fixed name can be traced to the certification of property rights and the need to keep accurate information on individual citizens through birth registers and certificates (Finch 2008, 711).

One can read inclusive language propositions and gestures as a way of unbounding gender-isation in a similar way that intersectionality has unbounded the individual functioning of the traditional categories of gender, race and class. This proposition can be read as one in which the processes of identity and individuation somehow take place in excess of systems of (social) classification. In this way then, persons can, both arithmetically and grammatically, become addressable, identifiable and named only in relation to themselves and not in relation to others at any point in time. This possibility has an affinity with what some marketing theories propose in relation to infinite regress processes of customization, a market or a grammar of and for one (only). The social consequences of such an experiment still remain, in my view, both politically and conceptually underexplored.

References

Finch, J. (2008). Naming Names: Kinship, Individuality and Personal Names. Sociology 42(4), 709-725.

Haraway, D. J. (1991). Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. London: Free Association Books.

Strathern, M. (1988). The Gender of the Gift. California: University of California Press.

.

.

How does personalisation relate to the existence of the person? Algorithms developed for personalisation intersect in a strange way with algorithms dedicated to the generation of people who do not exist. We find ourselves in a scenario where algorithmic mediation allows for not only the personalisation of various things, but also the personalised creation of persons. This question comes to mind when thinking about a genre of deep learning models so-called generative adversarial networks (GAN) and the recent enthusiasm about

How does personalisation relate to the existence of the person? Algorithms developed for personalisation intersect in a strange way with algorithms dedicated to the generation of people who do not exist. We find ourselves in a scenario where algorithmic mediation allows for not only the personalisation of various things, but also the personalised creation of persons. This question comes to mind when thinking about a genre of deep learning models so-called generative adversarial networks (GAN) and the recent enthusiasm about

One woman said that attending a science café is like peeking behind the curtain to understand what takes place backstage.

One woman said that attending a science café is like peeking behind the curtain to understand what takes place backstage.

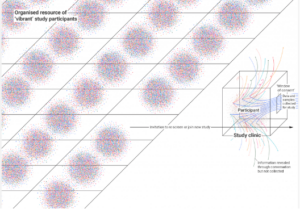

Just as jet engines now carry hundreds of sensors that track, model, and predict engine behaviour, digital twin developers envision the use of wearables, such as watches, socks, implanted and ingestible devices, which can gather situated data and give shape to a person’s digital twin. While the ‘virtual’ status of a digital twin – which one might assume to be a faithful and precise representation of a living person – is core to its advantage and potential use, the promise of precision requires extensive material resources. While the twin is viewed as digitally adaptive, updated, ‘smart’ – the sources of data must be standardised and compliant to stream updates according to specific timelines. The liveliness of the digital twin depends on its real life

Just as jet engines now carry hundreds of sensors that track, model, and predict engine behaviour, digital twin developers envision the use of wearables, such as watches, socks, implanted and ingestible devices, which can gather situated data and give shape to a person’s digital twin. While the ‘virtual’ status of a digital twin – which one might assume to be a faithful and precise representation of a living person – is core to its advantage and potential use, the promise of precision requires extensive material resources. While the twin is viewed as digitally adaptive, updated, ‘smart’ – the sources of data must be standardised and compliant to stream updates according to specific timelines. The liveliness of the digital twin depends on its real life

bare Minerals Made 2-Fit foundation

bare Minerals Made 2-Fit foundation